The first 10 years of the 21st century were my second full decade of writing about figure skating. For me, that included on-the-scene coverage of, among other things, both Olympics, all 10 U.S. Championships and seven World Championships.

It was the decade in which a brouhaha about the pairs result at the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City brought a massive change to the judging and scoring system.

The change, dumping a seemingly timeless system based on 6.0 as perfection, was intended to quantify the sport to a degree that it would bring fairer results. The unintended consequence was to overwhelm audiences with so many numbers that the results became nearly incomprehensible to even regular followers of the sport.

It was also a decade in which I got my first live looks at three of the most gifted women skaters I have covered, all three leaving indelible initial impressions of the careers that would reveal the utter brilliance of Yuna Kim, the ethereal lightness of Mao Asada and the eye-catching movements of Sasha Cohen.

In recalling my most striking memories of the aughts, let’s have the first impressions first:

The Beautiful Skating of Sasha Cohen

In my years covering figure skating, no senior national debut produced a more compelling performance than Sasha Cohen’s at Cleveland in 2000.

Her short program, to the lush, lyrical flow of the Albinoni “Adagio” and the pulsating notes of “Winter” from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, included eye-catching body positions of exquisite refinement and creativity. She displayed a depth of musical understanding rare for skaters, even knowing that both pieces are in a minor key.

Cohen, then 15, beat Michelle Kwan and Sarah Hughes in that short program before finishing second to Kwan after the free skate. In those 2 minutes, 45 seconds, all the qualities that made Cohen such an extraordinarily beautiful skater were on full display.

“We never let disciplined choreography get in the way of her natural movements, which often are better than set choreography,” her coach, John Nicks, said. “She is unable to get into an ugly position.”

But for the rest of her career, Cohen would be frustrated by her inability to do back-to-back technically strong programs. Never was that frustration more evident than at the 2006 Olympics, when she took a small lead into the free skate but botched her first two jumping passes. A month later, a badly flawed free skate cost her the World title.

Watching Asada a Revelation

Only an inconsistency in eligibility rules at the time, with one minimum age for the Grand Prix circuit and a higher one for the Olympics, kept Japan’s Mao Asada from contending for the gold medal at the 2006 Olympic Winter Games, in a season during which she won the Grand Prix Final.

Asada began the next season with a Skate America® short program that defined the essence of the skater she was and would be.

It was one of those moments to remind everyone why this sport can be so extraordinary, when a skater fuses art and athleticism with consummate ease into a performance that transports an audience to a state of stunned admiration.

Skimming across the ice with feathery grace, floating through her powerful jumps, Asada echoed in her movements the unadorned eloquence of the Chopin nocturne to which she was skating.

“She became that music,” said 1968 Olympic champion Peggy Fleming, commentating for U.S. television.

On the ice, she became lighter than air, able to launch herself into triple Axels, combining technical grit with refined grace. She landed no triple Axel at 2006 Skate America and finished third overall after a bumpy free skate but seeing her live for the first time in that short program was a revelation.

Kim Possessed a 'Special Quality'

In March 2007, Yuna Kim made history as the first World medalist from South Korea.

In my mind, that bronze medal in Kim’s senior Worlds debut was a footnote to a short program skate that not only produced the highest score in the five-year history of the sport's new judging system but was the moment Kim, then 16, began to command the world stage.

Kim came to Tokyo with chronic back pain that she belied with her strong jumps (opening with a triple flip-triple toe combo at a time when triple-triples were not yet routine in women’s short programs) and expressive gestures. She flouted both the pain and her youth by skating with an uncommon blend of power, elegance and maturity.

“She is always astonishing,” her coach, Brian Orser, said as Kim went from interview to interview in the media mixed zone.

Kim would underscore that over and over again. By the end of the decade, she was World champion.

“I’m completely impressed," said 1992 Olympic champion Kristi Yamaguchi of Kim’s win at the 2009 Worlds. “Her whole package — power, speed, jumps — is captivating to watch. She definitely has a special quality."

And the best was yet to come.

Gold at '05 Worlds Meant Everything to Slutskaya

In the summer of 2001, I met Irina Slutskaya for an interview over dinner at a Japanese restaurant in Moscow. Over the next two hours, as she spoke at length in occasionally fractured but wonderfully idiomatic English, I found her funny, open and as good a dinner companion as she was a subject of a story that would appear in the Chicago Tribune the week before the 2002 Olympics began.

By the end of the 2001 season, Slutskaya had been second to Michelle Kwan in three World Championships and third to Kwan in another. She had done that despite recurrent back problems and the burden of paying the medical bills for her father’s three spinal operations and seeing him hospitalized for nearly six months.

Before the next time I saw Slutskaya in Moscow, she had won a 2002 Olympic silver medal she insisted should have been gold and then her first World title. She chose to stay home with her ill mother rather than defend that title in 2003. Then Slutskaya had been diagnosed with systemic vasculitis, an often-debilitating illness that left her staggering into ninth place at the 2004 Worlds.

She had battled through that and, in March 2005, at the first World Championships in Russia since 1903, Slutskaya had a triumph that left her laughing and crying as she took her bows after the free skate. Everyone there felt some of Slutskaya’s emotions as she won all three phases of the first World meet to be scored with the new judging system, with Kwan finishing fourth.

“This gold medal is the dearest in all my collection,” Slutskaya said.

How could it be otherwise?

A Gentle Kiss to Say Thank You

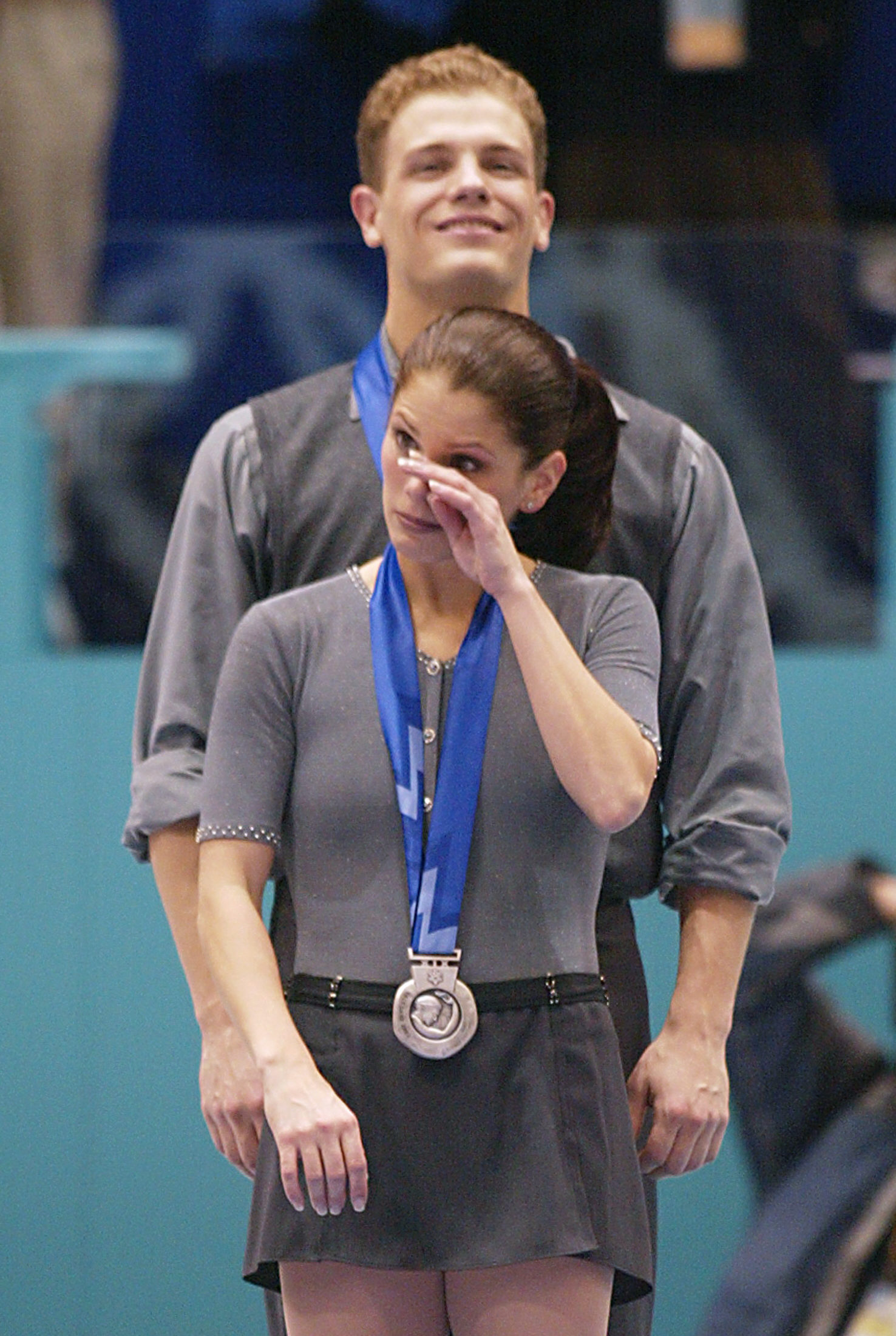

The skating was done, the bows were taken, the judges’ scores were yet to come. But Russian pairs skater Maxim Marinin did not want to leave the ice at the Turin, Italy, arena without showing his partner how he felt about her, with 8,000 people as witnesses.

Marinin dropped to his knees in front of Tatiana Totmianina, took her hands in his and then kissed them, ever so gently, ever so chivalrously. He looked like a nobleman paying homage to his queen, but this was so much more than a protocol gesture to the woman with whom he had just won the 2006 Olympic pairs figure skating gold medal.

“I think he made that moment to say thanks to me because we got through terrible days together, got back on the ice together, finally got the medal,” Totmianina said. “It was about a lot of things.”

One of those things was an accident so frightening that a U.S. judge who saw it from rink side initially feared Totmianina might have been killed.

Totmianina, then living in Chicago and training in its suburbs, suffered a concussion, black eye and multiple bruises on the arm Oct. 23, 2004, after falling eight feet to the ice when Marinin stumbled and dropped her from a lift at Skate America® in Pittsburgh.

Video of the fall drew worldwide attention. So when Totmianina returned to Chicago, the 22-year-old did interview after interview as a means of proving she still was alive. She was able to return to practice well before Marinin, who blamed himself for the accident and needed weeks of intense work with a sports psychologist to get past the terror of it happening again.

“With good things, you couldn’t become famous,” Totmianina said, sardonically.

Sixteen months later, she and Marinin proved the opposite.

Lysacek Under the Radar

Evan Lysacek came to the 2005 World Championships hoping only to make the 24-skater cut for the free skate. He wound up with the bronze medal, making him the first U.S man to win a medal in his senior World debut since 1991.

After short program errors wound up costing him a 2006 Olympic medal (he was fourth), Lysacek seemingly was far from medal contention at the anticlimactic post-Olympic 2006 Worlds after another botched short, but he rallied to get a second straight bronze.

In 2007, when Lysacek won his first U.S. title with one of the most dazzling technical free skates in that meet’s history (one quad, two triple Axels among his seven triples), the event in Spokane ended so late (after 1 a.m. on the East Coast) that few heard what he had done until a day after — if at all.

“This,” said four-time World champion Kurt Browning of Canada about Lysacek’s free skate, “was a clinic.”

In 2008, the story was not how Lysacek won his second title but the unlikelihood of needing a tie-breaker to decide the title (the free skate result) because he and Johnny Weir both had 244.77 points — the only such tie for a medal in any discipline since the IJS was first used at the U.S. Championships in 2006.

At the 2009 Worlds in Los Angeles, Lysacek caught no TV scheduling breaks, either, with the men’s final on a Thursday having been shown on a network called Oxygen and, once again, ending around 1 a.m. in the East.

Even with his triumph at the 2009 World Championships, Lysacek’s achievements kept flying under the radar.

This time, though, what Lysacek did merited a replay during NBC’s prime-time Saturday telecast of the women’s final.

So a much bigger audience got to hear the standing ovation that started 10 seconds before the end of Lysacek’s program and turned into a roar as he put his hands on his head in an expression of delighted disbelief over becoming the first U.S. man to win a World title in 13 years.

Skating to Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” he cleanly landed eight triple jumps, spun effortlessly, received positive grades of execution on 12 of 13 elements, and a neutral grade on the other and was rewarded with the highest level for all of his spins.

“I was trying not to get too excited with each element, but I kept wanting to throw my hands in the air,” Lysacek said.

So a year later, at the Vancouver Olympics, the radar would be pinpointing him. And, as was the case for 2009 women’s World champion Yuna Kim, the best was yet to come for Lysacek.

Kwan Bids Painful Farewell at Press Conference

The last of the hundreds of Chicago Tribune stories in which I covered Michelle Kwan as a competitor did not come from part of a competition.

It came, alas, from the Turin, Italy, press conference in which Kwan, then 25, talked about the painful decision she had made a few hours earlier to withdraw from the 2006 Olympics.

I knew that for all intents and purposes, it was also a retirement announcement for the most decorated and beloved figure skater in U.S. history, the greatest skater ever whose career would not include an Olympic gold medal.

That press conference came a day after Kwan cut short her first practice in Turin, skating 24 difficult minutes of an allotted 40, and left in tears after falling on four of five triple jump attempts. The proximate cause was a groin injury that had kept her from Olympic-style competition since a fourth-place finish at the 2005 Worlds and had led her to petition successfully for an Olympic spot. But her body appeared to be generally giving in to the pounding of 13 years as an elite senior skater and the increased technical demands of the new judging system.

“I have tried my hardest,” Kwan said at the press conference. “If I don’t (ever) win the gold, it’s OK. I’ve had a great career. I’ve been very lucky.”

In the 2000s, Kwan added an Olympic bronze to her 1998 silver, won six more U.S. titles for a record-tying nine, five more World medals (three gold, one silver, one bronze) also for a total of nine (5-3-1) — three more than any U.S. skater has ever won.

“If people take time to look at her body of work, that equalizes the one thing she doesn’t have,” 1988 Olympic champion Brian Boitano said.

In the 2000s, the Kwan performance I remember most vividly came in the free skate at the 2004 Atlanta U.S. Championships. Full of emotional fire, more confident and solid in her jumps than ever, she brushed away short program winner Sasha Cohen’s presumed challenge.

“I’m afraid I’ll keep on skating and skating and skating, and I’ll forget I’m not 20 anymore,” Kwan told me in a phone conversation a week before the 2004 U.S. Championships. “I want chapters in my book, not just one long chapter.”

The skating chapters ended with the press conference in Turin. The subsequent ones have included work as the candidate’s surrogate on two presidential campaigns (the latter Joe Biden’s), bachelor’s and master’s degrees, a public diplomacy envoy role for the State Department, a senior advisor’s job at State and a Special Olympics global ambassadorship. In writing about those, I have felt that as remarkable as Kwan’s career as a figure skater had been, what she has done since is even more impressive.

My Take on That Pairs 'Thing'

There was that pairs thing at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City.

No matter who apparently tried to corrupt whom, Russians Elena Berezhnaya and Anton Sikharulidze deserved the gold medal they wound up sharing with Canadians Jamie Salé and David Pelletier.

Giving a second gold to the Canadians was an expedient ex post facto decision demanded by the International Olympic Committee. The IOC wanted to prevent the rest of the Games from falling into the maw of an extended controversy fomented by television commentary and foaming-at-the-mouth Canadian Olympic officials.

Never before had a second Olympic gold medal been given to rectify a problem caused by a judge’s alleged misconduct in a subjectively judged sport.

Oh, how this might have been avoided if only Salé and Pelletier had revived their magnificent “Tristan and Isolde” free skate program from the previous season when they decided to switch programs not long before the Olympics.

Instead, it was back to the 2000 program with the schlockfest of themes from that soap-operatic movie Love Story, while the Russians performed to the pure, elegant romanticism of “Meditation” from the Massenet opera Thais.

The North American audience preferred error-free schmaltz. Five of the nine judges did not.

The Russians’ seamless flow, beautiful edge work and connecting movements, and understated skating won out on presentation scores, their one flawed jump landing an insignificant blip.

Case closed.