Above: Yamaguchi and her grandparents, George and Kathleen Doi, celebrate the skater’s success at the 1988 NHK Trophy in Japan. She finished second to Japan’s Midori Ito and earned the bronze in pairs with Rudy Galindo.

The following story appeared in the May issue of SKATING Magazine.

By Barb Reichert

Kristi Yamaguchi does not take the phrase “American dream” lightly. Her family’s story, rooted in one of the most shameful chapters in American history, is one of sacrifice, service and perseverance.

As an Olympic champion, philanthropist, author and cultural icon, Kristi was among the first nonwhite female athletes celebrated on a large scale. An inspiration for many Asian Americans, her family’s story makes it even more meaningful for a young Kristi to have been embraced by white Americans three decades ago and later as the winner of “Dancing With The Stars.”

A trailblazer? Yes. But she’s not the first trailblazer in her family.

That honor goes to her grandfather, George Akira Doi, who fought for his county during World War II while his pregnant wife and other members of his family were incarcerated by the U.S. government.

Their crime? Being Japanese American.

“I think some of us today have no understanding of how much they endured,” Kristi said of the estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans who were forced from their homes and incarcerated despite not being charged with a crime. “Going through war, yes, but also being Japanese Americans who were so determined to prove their loyalty to a country that was not treating them [justly].

“I’m very grateful for their determination, their resiliency and their loyalty to allow literally one generation — someone like me — to live the American dream.”

A NISEI SOLDIER

George Doi was born in California to Japanese immigrants from Saga Prefecture. George and his younger brother, Frank, were Nisei (first-generation Japanese Americans) who grew up near the beach in San Diego. While studying engineering at the University of Southern California, their father, Bunjiro, died, leaving their mother, Tokue, a widow, and George as the head of the family.

At age 26, George was inducted into the U.S. Army in 1941. Ten weeks later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, thrusting America into World War II and unleashing the fear and racism that resulted in the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Six weeks after the attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which, according to the National Archives, “authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to ‘relocation centers’ further inland, thus resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans.”

On March 21, 1942, Congress quickly passed the law, which was supported by nearly 60 percent of Americans, who feared Japanese Americans would actively sympathize with Japan.

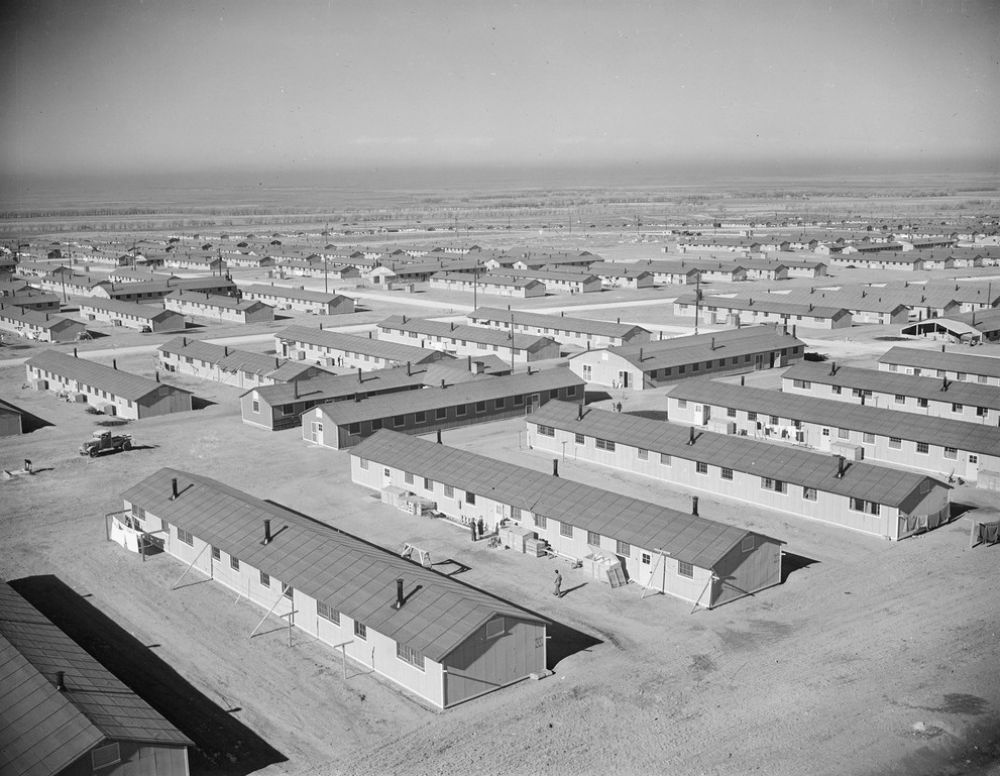

Both sides of Kristi’s family — the Yamaguchis and Dois — were forced from their homes and sent to internment camps, which were enclosed by barbed wire and armed guard towers.

Grandparents Tatsuichi and Tsuya Yamaguchi, who lived in a lush Central California farming community, took only what they could carry when they and their eight children (including Kristi’s father, Jim) were forced to relocate to arid Poston, Arizona, where the nation’s largest of 10 internment camps was built on the Colorado River Indian Reservation.

Meanwhile, the Dois were being forced from their Southern California beach community to be incarcerated at Camp Amache in Granada, Colorado, a dry, wind-swept prairie near the Kansas border.

During his service stateside, George met and eventually married Kathleen Kobata. Due to his exemplary service, Kathleen was released from the Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming, but voluntarily returned to a camp due to hostilities against Japanese Americans.

“My grandmother actually spoke very little of that experience,” Kristi said. “That was kind of typical of that generation, not wanting to talk about it.

“But while she was free, there was such anti-Japanese American sentiment that my grandmother couldn’t get a job. It was just a difficult situation to even find a place to live. When she found out she was pregnant, she went back into the camp on her own accord so that she could be with her family and her parents [who were all at Amache]. She just felt safer there.”

With his family incarcerated, George — the only Japanese American in the all-white 100th Infantry Division — led soldiers through the mountains of France and into Germany for six months against a heavy counterattack. His commander, Capt. James Dougherty, called him “unquestionably the company’s best soldier,” and promoted him to second lieutenant.

While her husband fought in Europe, Kathleen gave birth to Carole — Kristi’s mother — on Jan. 1, 1945, at Camp Amache.

Although Carole was too young to remember living in the camp, she recalls her mother Kathleen’s stories.

“She didn’t like it in the camp,” Carole shared through Kristi. “It was really dusty and cold. It was hard always eating in the mess hall together. It really fractured family units because it was harder to keep a ‘family meal’ together [because] kids went off to eat with their friends.”

A NEW FUTURE

After George’s promotion to second lieutenant, Kathleen and infant Carole were released early from Amache and resettled in Gardena, California. In 1946, George joined his new family and opened an auto repair shop. He and Kathleen had two more children, Gary and Nancy.

“My dad tried to assimilate the family, so none of the children were given Japanese names and they were never taught the Japanese language,” Carole said through Kristi. “He really wanted to show his loyalty to his country that he grew up in and fought for.”

Like many Japanese Americans of the time, the Doi family endured hardships but became valuable members of their community. As the years passed, and their children married, George and Kathleen became loving grandparents — and skating fans.

“At the beginning, they didn’t understand my commitment,” Kristi said. “They were like, ‘What do you mean she’s going [to skate] before school every day?’ But then I think when they saw how dedicated I was, that’s when they really started to understand.”

Kathleen and George traveled to many of her competitions, including several NHK Trophy events in Japan.

“They were very proud grandparents,” Kristi said.

George died in 1989 at age 73 but lived to see his granddaughter named to her first U.S. World Team. Kathleen, who died in 1999, shared in the joy of Kristi’s 1992 Olympic championship over Japan’s Midori Ito.

SACRIFICE HONORED

In 2010, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to the Nisei soliders of the 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the Military Intelligence Service.

Second Lieutenant George Doi is among the 12 Nisei soldiers featured in the Smithsonian’s Congressional Gold Medal Exhibit in Washington, D.C. He also received a Bronze Star for “meritorious service in support of combat operations” as the de facto platoon leader of soldiers who were engaged in 163 consecutive days of combat.

On Feb. 19, 2022, the U.S. Government declared a “Day of Remembrance of Japanese American Incarceration During World War II.” The declaration states, in part: “We acknowledge the unjust incarceration of some 120,000 Japanese Americans, approximately two-thirds of whom were born in the United States. … Today, we reaffirm the Federal Government’s formal apology to Japanese Americans whose lives were irreparably harmed during this dark period of our history, and we solemnly reflect on our collective moral responsibility to ensure that our Nation never again engages in such un-American acts.”

Carole states it more bluntly: “An American family and children should never go through being stripped of their civil rights as they were because of Executive Order 9066.”

Camp Amache was closed on Oct. 15, 1945, six weeks after Japan surrendered to end World War II.

On that day, the remaining 85 Japanese Americans were set free.