By Ryan Stevens

In the 1940s, skaters from around the world rallied in the war effort. Countless American skaters served in the military, including such champions as Robin Lee, Eugene Turner, Bernard Fox, Bobby Specht, Ollie Haupt Jr., Al Richards, Skippy Baxter and Walter Noffke.

The increased number of skaters who entered the military had an extreme effect on the American figure skating community. With so many young men drafted and transplanted to other parts of the country, one club’s loss was another’s gain in some cases, but in others, promising careers were cut short by their service.

The U.S. government took over many rinks to use as drill halls and storage areas. Some clubs turned to outdoor skating on ponds or frozen tennis courts. Gas rationing, tire shortages and bans on pleasure driving for non-essential purposes in some areas made it hard for members of clubs to travel to skate in other areas.

Most clubs provided free or discounted ice time to men in the service.

The United States Figure Skating Association had a Trophies Salvage Committee. Skaters past and present were encouraged to donate old pewter trophies and medals to be melted down and manufactured into war equipment. Clubs were required to pay for gold test medals earned, and the production of new medals and trophies was limited.

Skating clubs sold war bonds, made bandages and donated proceeds from carnivals to the Red Cross. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Philadelphia Skating Club and Humane Society arranged for a mobile unit of the Red Cross to visit its club. Skaters donated more than 265 pints of blood. SKATING magazine donated typewriters to the military.

Many women were engaged in war work. One skater whose life was directly affected by the attack on Pearl Harbor was U.S. and North American champion Joan Tozzer. At the time of the bombing, she was living in Honolulu, where her husband was serving in the military. Her son later recalled hiding under a bed with his nanny during the attack. After the U.S. joined the war, Tozzer enlisted in the Army’s Women’s Air Raid Defense and the USO, aiding in the war effort by working in a top-secret, underground mapping program.

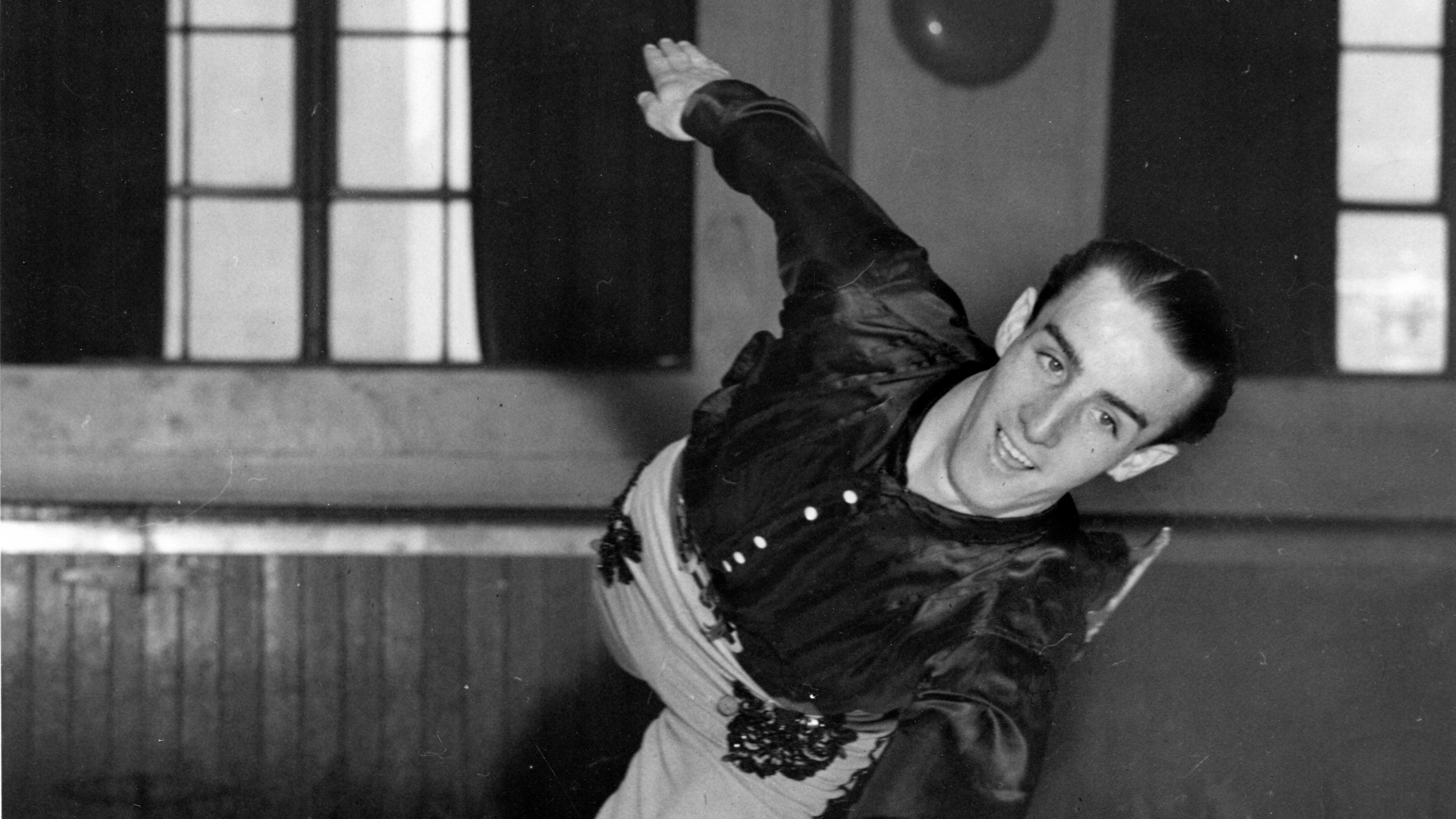

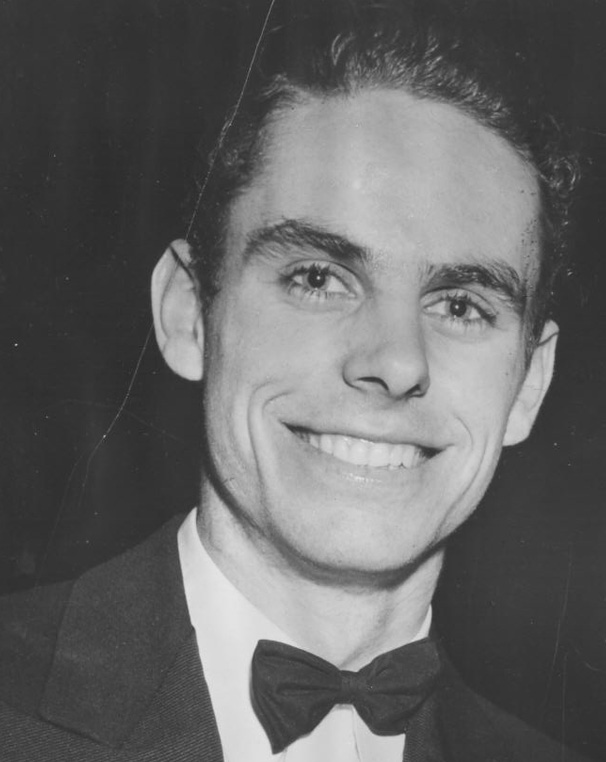

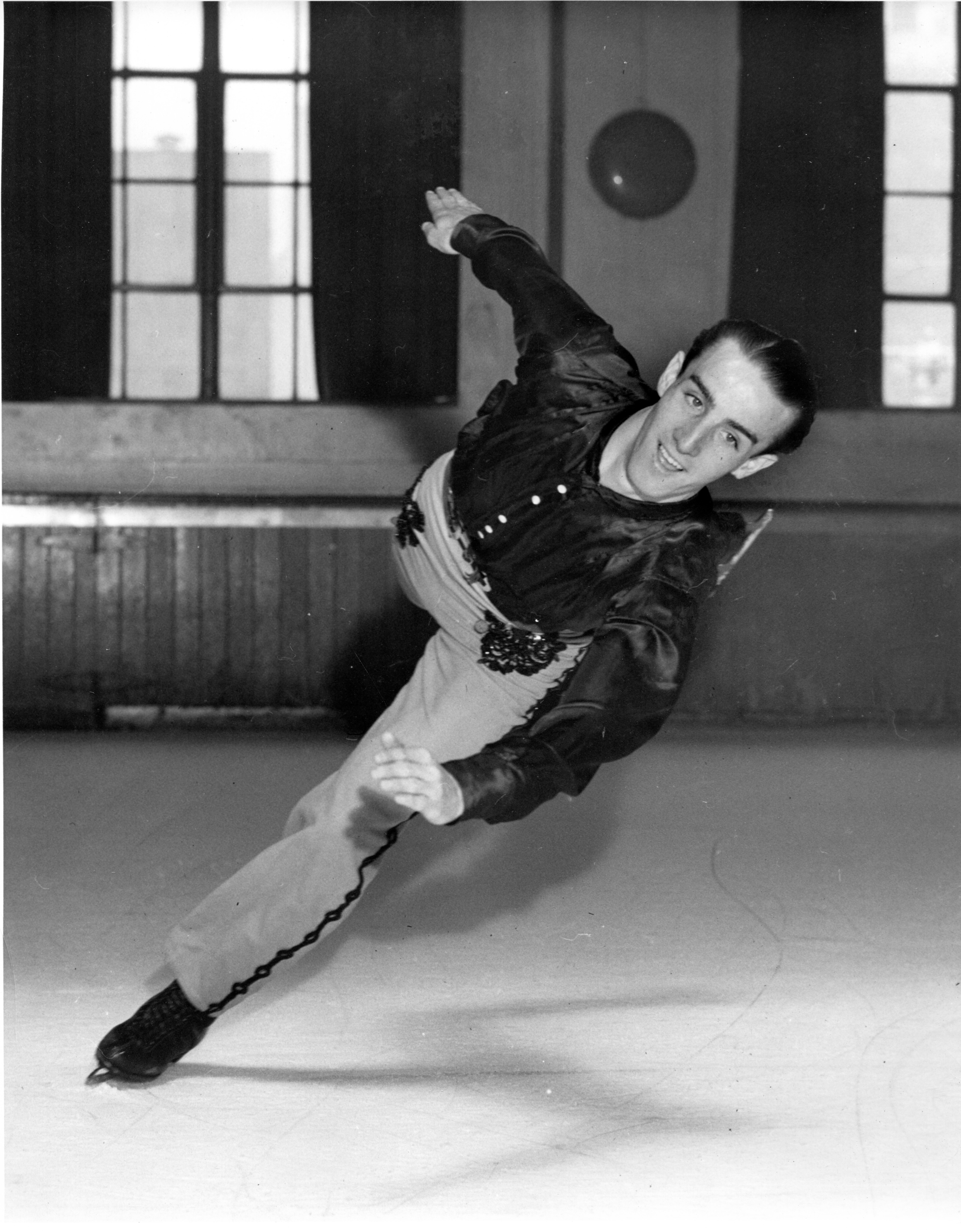

Winfield A. Hird, the managing editor of SKATING magazine prior to the war, was killed in China in 1943 as a member of the U.S. Air Force. British figure skater Freddie Tomlins, the 1939 World silver medalist, was killed while serving with the Allied Forces. He was quite familiar to American audiences because he did his training in Canada and skated in quite a few carnivals in the United States around that time. He was known for his huge jumps.

Across the ocean, Londoners were forced to subsist on meager rations, and contend with fuel oil shortages and gas rationing. They spent more of their time doing war work and running at the sound of sirens to their Anderson shelters than they did living normally. For some, figure skating was their sole escape from this dreary existence, and the Richmond Ice Rink was their mecca.

Allied servicemen from all over the world insisted that it be kept open. So special was the rink considered — a meeting place of discipline, excellence and fun without alcohol — that the government made a special order to black out the 500-foot-long building to allow it to remain open. After all, the Richmond rink was an institution where more than 4 million people learned to skate. Despite the blackout efforts, a 2,000-pound bomb was dropped on the rink’s engine room. Miraculously, it didn’t explode, thanks to some quick thinking by the rink’s staff.

However, the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, forced North Americans to wake up to the possibility of an enemy attack on home soil. Blackout drills were advertised to U.S. citizens in advance, and by 1942, blackouts became the norm on the West Coast. In early 1942, Tozzer wrote to SKATING magazine editor Theresa Weld Blanchard, explaining, “We have breakfast at 7, lunch at 12 and supper at 6, as the blackout starts at 7:30. If you are asked to go out to dinner, you go at 5, eat at 6, and get home by 7:30 unless the hostess is kind enough to ask you to spend the night.”

The 1945 North American Championships at Madison Square Garden were skated under wartime/blackout conditions as well. The entire building had to be cleared and lights out before midnight. This forced a delay in presenting medals and trophies to skaters.

SKATING magazine nearly doubled its subscriptions during wartime, and Weld Blanchard recommended that the magazine be sent free of charge to members in the military. Those serving often wrote in to express just how much reading about skating lifted their spirits and gave them something to look forward to when (if) they came home.

Ryan Stevens is a former figure skater living in British Columbia. He won four medals at the Nova Scotia Provincial Championships before turning to judging. Since 2013, his passion for studying unique and, at times, obscure aspects of figure skating’s history has led him to write hundreds of articles for the blog Skate Guard. He’s also penned a biography of British skater Belita Jepson-Turner and features on skating during the Edwardian era and Great War. He’s been consulted for research about skating history for CBC, NBC, ITV, print projects and numerous museums and archives in Canada and Europe.