National Get Up Day is Feb. 1. Through the month of February, U.S. Figure Skating will be featuring its eight Get Up ambassadors. The following story appeared in the January issue of SKATING magazine.

By Ed Rabinowitz

Figure skating was Caroline Park’s world, and she flourished in it.

“Her training skills were so good, and her programs were so beautiful,” recalls Tim Covington, a master-rated figure skating coach. “I always tell the kids I’m training, that it takes a lot for me to notice somebody else during one of their lessons. And I would constantly notice Caroline.”

“Her training skills were so good, and her programs were so beautiful,” recalls Tim Covington, a master-rated figure skating coach. “I always tell the kids I’m training, that it takes a lot for me to notice somebody else during one of their lessons. And I would constantly notice Caroline.”

But in October 2017, Park was diagnosed with a pars fracture on her lower spine. She took a few months off, but then an MRI revealed that, in addition to degenerating discs in her lower spine, she had a major herniated disc that needed immediate repair.

At age 13, Park was crushed.

“I felt rudderless for a while,” she says. “I knew deep down inside skating was something I really wanted to get back to, but didn’t know if I would physically be able to do so.”

In 2018, Park entered her freshman year of high school despondent that she could not participate in sports. More importantly, her pain worsened and began spreading to all of her joints.

“Some days I couldn’t even get out of bed,” she says.

Over a two-month period Park saw 15 doctors, none of whom were able to provide a conclusive diagnosis. Some suggested Park was psychosomatic.

“They kept saying [the pain] was in my head,” Park says.

Finally, in early 2019, a basic X-ray, followed by an MRI and CT scan, revealed that Park had severe hip dysplasia in both hips. She was eventually diagnosed with Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a connective tissue disorder that causes her joints to move too freely and dislocate often. Reconstructive surgery on each hip, six months apart, followed.

Park spent the next 18 months in physical therapy. She had to relearn how to bend and flex her feet. It was a challenging time, but one she says was also filled with triumphs, including joining her school’s varsity track and field team as a distance runner.

“Prioritizing my health became the most important thing,” Park says. “With EDS you need to have your muscles toned in order to keep your joints in. The whole ritual of running and conditioning helped me with my joint pain.”

Now it was time to return to the ice.

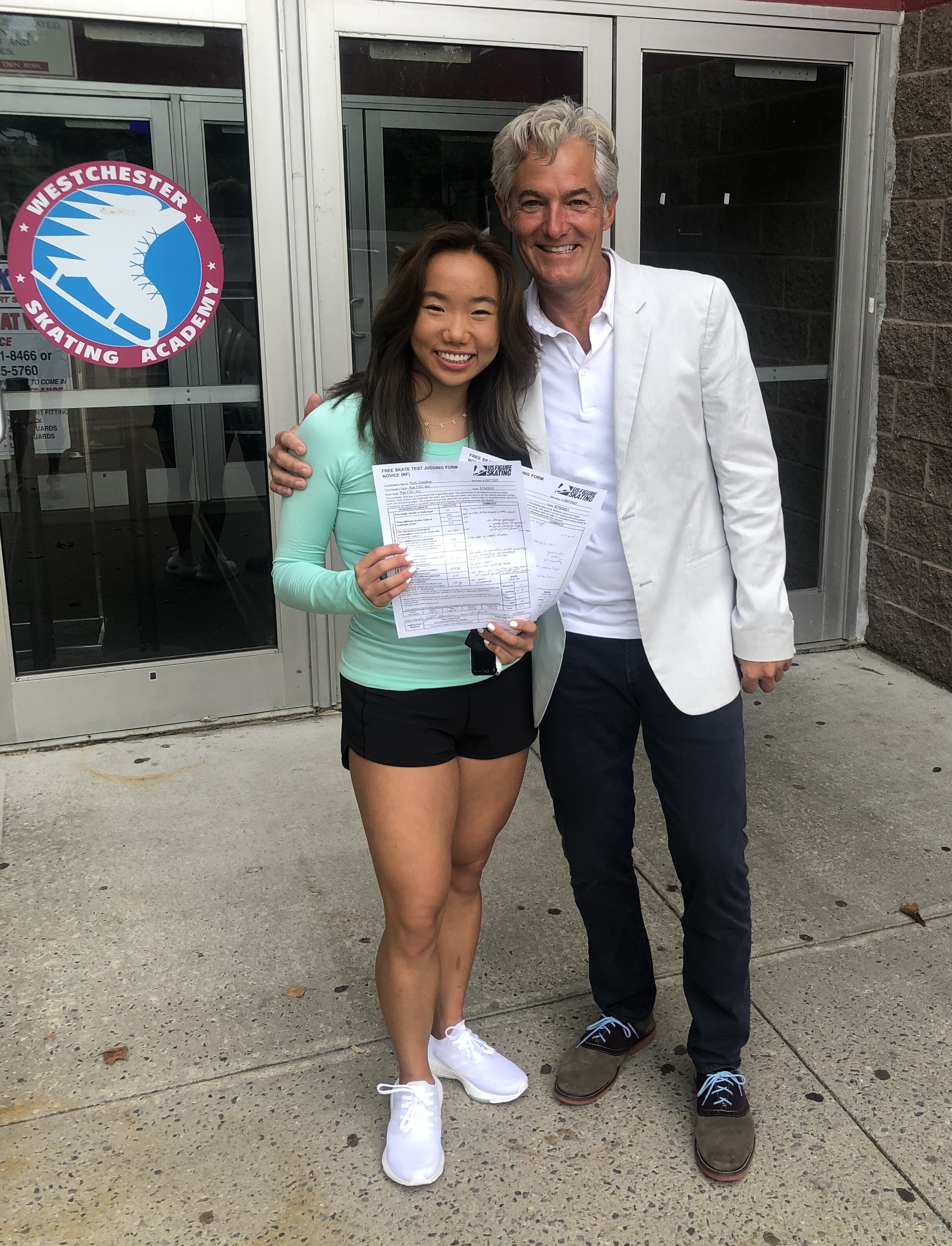

Park’s mother, Maine, a figure skating judge, approached Covington and asked if he would work with her. He admits he was apprehensive at first.

“I was overly protective,” Covington says. “It was hard at first to push her, but she wanted to be pushed. Initially we did everything in the harness, and I gradually backed off to the point where she was doing the jumps on her own.”

And doing them, he says, even better than before her injuries.

“For Caroline, this is unfinished business,” Covington says. “She’s a very determined young lady. And it was her dream to be a skater.”

By July 2021, just two years after reconstructive surgery on both hips, Park took and passed her senior moves-in-the-field test. She says her elements have improved as a result of her hips no longer being dysplastic, and she feels liberated being back on the ice.

“Wherever the heart goes, the body follows,” she says. “That was my case with skating. Especially having been [a wheelchair user], it means so much more to me now. I’ve learned not to take anything in life for granted.”

For Park, skating was never about the medals or standing on the podium. It was always about going to the rink each day, seeing her friends, spending time together on the ice, and bonding over their shared passion for skating. Park hopes to reconnect with those friends as she works her way through the college application process.

“I’m looking at a lot of colleges right now, some with really incredible teams,” Park says. “Some have my old figure skating friends on them, so that would be exciting if I could spend more time with them.”

Regardless of which college she chooses, Park says skating will always be something she does for herself, an outlet for when life gets hectic and she needs to ground and re-center herself.

“When I’m on the ice, I’m home,” she says. “I’m in a much better state of mind. And that translates into everything I do in life.”